Weeding the Wilderness

Reflections on Stewarding Beauty, Maturing Through Labour, and Life by Ordinary Means

Last week I spent hours weeding at a friend’s house.

And because I am not using my smartphone ( #90sSummer ) there was no ability to drown my thoughts out with eclectic guitar riffs from the 70s.

The grass and brambles had grown up through the stones and gravel and to get at their roots I had to dig my hand into the coarse and dry earth. You have to pull with a gentle force, as close to the base of the stem as possible in order to get all those creeping tendrils out. And when you pull you can hear the snaps—the fibrous limbs being torn away from dirt and rock and loam.

And you take this weed, green where it breathed above the earth, and brown and tan where it dug deep below, and you throw it into a bucket. And you do it again, about a million times, until the walkway is clear.

And somewhere around weed three-hundred-twenty-four-thousand-six-hundred-and-eighty-nine, you settle into a cadence. The mind turns off, your knees grow callous to the edges of rock, your hands gritty and a bit bloody.

And about fifty-thousand weeds after that you start thinking fresh thoughts.

I was thinking about the parable of the sower and the weeds and the stoney ground.

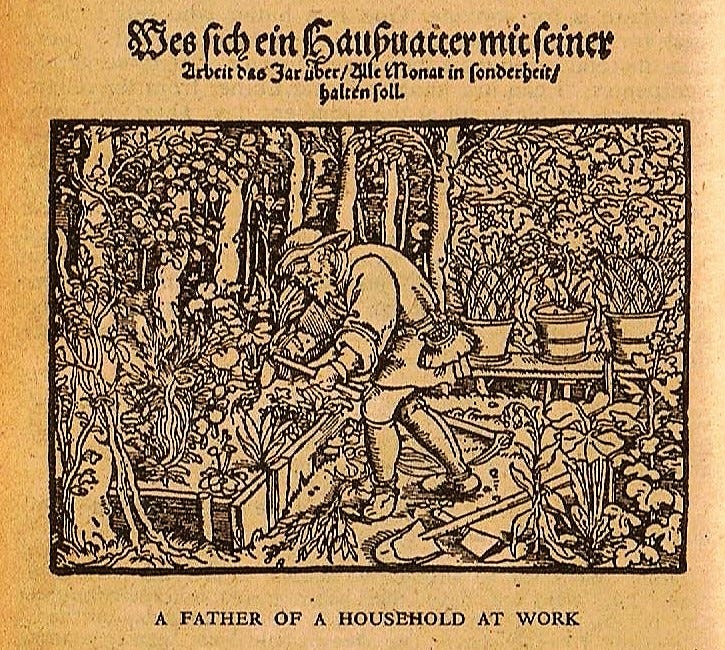

I was thinking of Adam and the wilderness and the Garden.

I was thinking of my own chores as a child.

And I was thinking of the cost of Beauty.

The sun was slow-cooking my shoulders and neck, the hum of the neighbours central air unit was buzzing in a whooping tempo; flies droned at my ears and bugs scurried away as I unearthed their homes.

And on it goes.

Beads of sweat hang off my eyebrows, my mouth is that tacky kind of dry, the kind you get after eating three day old cornbread, the kind that’s thick at the corners of your mouth.

And I’m not even half done.

And around weed six-hundred-thirty-three-thousand-four-hundred-and-seventeen your mind turns back on.

Goodbye flow.

Hello back pain.

And the romance of it, of hands in dirt, of taming the earth, that’s gone.

All that remains is the curse; by the sweat of your brow, or whatever.

And I remember pulling out weed nine-hundred-ninety-nine-thousand-nine-hundred-and-ninety-nine. I remember standing up, doing that weird stretch we all do, where you put your hands on your hips, plant your feet in a wide stance, and push your buttocks forward. I remember wiping sweat away from my forehead with dusty hands, and I remember staring at that last weed — a kind of smug victory on my face.

I had a mason jar in my car, filled with water and lemons and cucumber and raspberries — some infusion my wife made — and I left that last weed there while I went and quenched my dustbowl thirst.

The water was cold and tart and had the round sweetness of cucumber; I could feel it river through me, down each laneway of my body, filling up my cells like water-balloons.

And I went back to that weed a new man.

Tired but satiated.

I plucked that last weed, one million, and tossed it into the bucket — its plastic grave.

And it’d be just a few weeks before they’d be back. So it goes, I think.

1. Stewarding Beauty

Okay, you got me, there wasn’t a million weeds, probably not even a hundred thousand; but the weeding took blood and sweat and time. So, there’s that.

And I think all beauty requires that — the blood, the sweat, the time.

Stewarding beauty, or in the common tongue, weeding, is a priestly duty — a divine vocation. It’s not some luxury we indulge in, and even if we are rich enough to pay someone else to do our dirty work, it’s still some-body who needs to do it.

There’s always gonna be a body somewhere along the line. Just ask the mafia.

Stewarding beauty is a liturgy : using our bodies to teach our entire person.

And life, like that stoney path, requires work — and that work, the process of making all things Beautiful, is a responsibility. We have a duty to tame the wild and bring the Garden of God to fullness — not for ornamentation sake, but as a kind of sacrament — some mystical participation in spiritual realities.

Making invisible things visible.

I like to think, in some small way, that freshly weeded rocky road glowed with heaven’s light for the rest of the day, and I imagine if someone walked it, they might just be healed of all their infirmities ( c.f. Peter’s shadow in Acts 5 ).

Doing Good work, Beautiful work, does more than some vague or nebulous internal transformation — it does a kind of external witnessing. Like the mountains and the trees singing their praises, the birds and the oceans that can’t shut up because of their joy. This gravel laneway just joined the chorus.

There’s this other thing about stewarding beauty — we have to cultivate it. The modern ethos, the chant of our contemporaries, is consume. We indulge in beauty and grow fat on pleasure.

But real Beauty requires cultivation.

Yards and gardens can’t be bought brand new every week when it’s time to cut the grass or prune the shoots. Some things can’t be replaced when all they need is some TLC. We have to keep the Beauty, maintain it, guard it. Do our chores.

It’s the same with the stupid laundry and the dusting.

It is hard to quantify the Good that comes from washing the darks and hanging them out to dry, hard to measure the Rewards of swiffering and feathering the bookshelves, the desks, the tables.

It’s easier to quantify by comparison. We feel the dread of things getting out of hand, of rank clothes piles and mutant dust-bunnies. And in those moments we learn the hard truth :

Beauty must be cultivated, always.

And think about this for a moment : I don’t know if it would have been proper to call that walkway a walkway while all the weeds were on it. Just like I can’t call a slab of marble a statue until I chip away all the extra.

Stewarding Beauty is a kind of purifying and naming — a giving or a restoring of identity and intention. Those weeds obscured the proper use of the gravel; made it a home for critters and webs and cigarette butts. But in the clearing, in the trimming, in the uprooting, things were made new.

That’s what I think Jesus was on about when He was talking about the vine and the branches and doing the work to remain in Him. I think the remaining looks a lot more like uprooting than we care to admit.

And listen, before I strain this metaphor beyond its breaking point — stewarding beauty is about the dishes, about washing your face, brushing your teeth, saying your prayers, and putting your laundry away. Those things, those small acts, reorder reality — tame it from some entropic zoo into some cathedral of home.

2. Maturing Through Labour

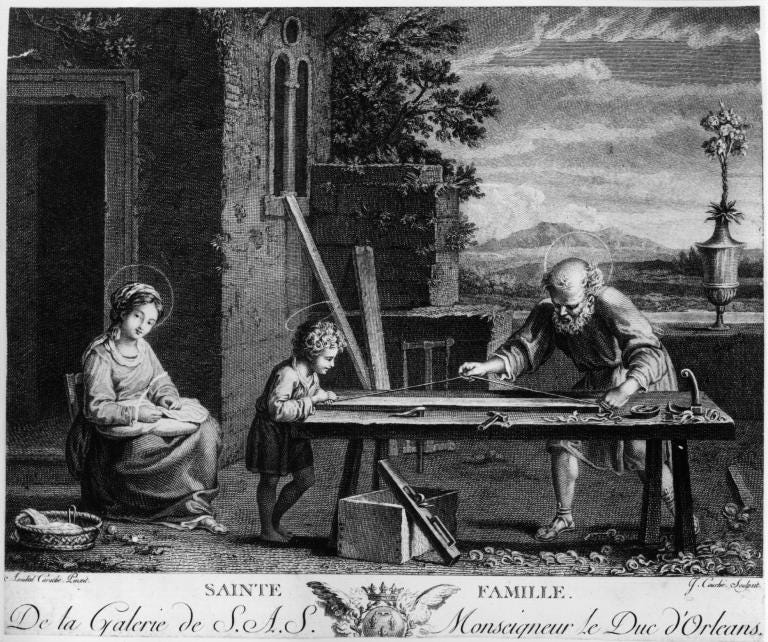

Our tale is as old as time — the Adamic story post paradise; the thorns and the brambles, the earth that strives against us, giving us the proverbial middle finger. But it is not just Adam’s story, we also see Mary the homemaker, Christ the carpenter, Paul the tentmaker, Josh the doodler.

We poo-poo strain, roll our eyes at housework and errands, and for some reason, the second I pick up the windex and one of those microfibre clothes to wipe down mirrors and windows, the strength is sapped from my body as in the heat of summer ( c.f. Psalm 32.4 ).

To be quite frank, our time is a childish one, venerating ease and instant gratification, indulging in entitlements that would make Enlightened French Aristocrats blush. And we wonder why culture seems to tantrum, to pout, to be stuck in the terrible twos.

It is because no one wants to put in the work.

We want short cuts for our whole life; everything as instant as our messaging ( take me back to the dial up days, pls ).

Here’s the thing about labouring : it matures you, or, in the theologians parlance, sanctifies you. Work trains your body, it trains your will, and somehow, in the midst of choosing effort over ease, we grow.

Nietzsche once wrote of a long obedience in the same direction, and evangelical renegade Eugene Peterson wrote a book by the same name. And I don’t think the phrase is too puzzling to riddle out, but I’ll explain it a bit, anyways.

Most of life is doing the same, few, small things, a bajillion times. Say your prayers every day. Your bible reading every day. The dishes, the laundry, the drive to work, the nine-to-five. Every. Damn. Day. Change the diapers, cook the meals, put them in Tupperwares with perpetually missing lids.

That’s it.

That’s life.

And even our absurdist hero Albert Camus had to imagine Sisyphus happy. And trust me, I have had my own boulders to push, only to feel them come rolling back down the slopes as my alarm goes off at 5am.

The thing is, in Christianity, life has meaning — not imagined, not practical, not Jungian, or forced, or conjured. The little moments aren’t desperate, not psycho structures to make sleep a bit easier — they’re real invitations into the infinite life of God ( c.f. my book ).

And one day, however, that stupid stone won’t roll back down, it will roll away, the same way it did with Jesus — for the old order of things shall pass away.

And one last thing. This slow, intentional maturity and effort is vital for a beautiful life. Think of the speed of mass production, of Ikea couches that fray and splinter in months, of plastic buckets that crack their second use at the beach, of jeans that go threadbare after a few washes.

And then consider craftsmanship and excellence — think of the artisan who builds a leather chair with his hands. I have two, actually, signed by the people who cut and fasted the wood, who stretched and sewed the leather — and they will probably outlast me, and be handed down to my kids.

Part of maturing, by Beauty, is learning that the slow and intentional lasts a heck of a lot longer than the phoney and the fast. There is something substantial about that growth, about that long obedience in the same direction — about the mastery of life. Because, you know, that finely crafted chair is also a metaphor for virtue — an excellent life, handed down.

3. Life by Ordinary Means

Like I said above, all of life is in the small things — or, in the lingua franca, the ordinary is holy.

Don’t wish away the alarm clocks, the parent-teacher meetings, the shovelling of the driveway. We were not made to cry over spilled milk, we were made to bring order to chaos — and sometimes that looks like a sheet of Bounty, the quicker picker upper, wiping down the dining room table.

I guess what I am trying say is that your ordinary life is sacramental; it’s the rhythm of the world, and you wage war against wilderness not by conniption and not by blow-ups or by resentful, sullen asperity.

No, that won’t help anything ( it only makes things worse ).

You wage war against the wilderness with Beauty.

You can reject the spectacle, the follows and likes and restacks, the desire for all kinds of virtual eyes, and you can lean into every normal and ordinary thing that makes us truly human. Contrary to popular belief, you do not need a big following to be a good husband, mother, friend, janitor, or writer. You don’t need a new city to fix you, you don’t need a new job or a better five year plan.

You only need new eyes — descaled ones — ones that see Reality clearly.

All of these ordinary days, the hum drum of it all, this is where your whole life resides, in them and through them. Each of these moments are invitations and gateways into God’s Life, if you would just accept it.

What I am trying to say is : The Ordinary Life is a Portal.

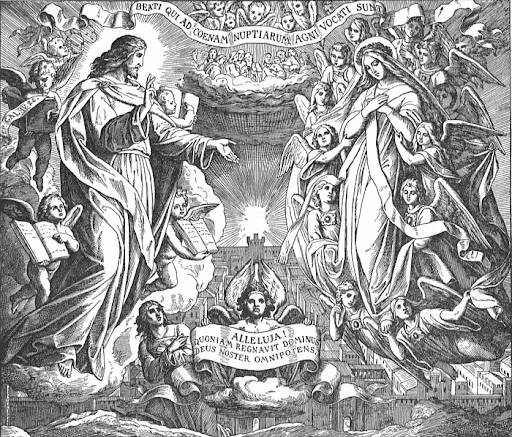

Your kitchen table is a kind of altar, meals are echoes of the coming Eternal Supper, sleep is some shadow of full Sabbath Rest — and weeding ? Well, that’s subduing the earth and making it flourish with the Beauty of God.

I guess I like to think that Heaven is Homemade.

I don’t think it’s outsourced to machines or underpaid labourers. I think Jesus laid the streets of Gold, brick by brick, and I think He used what His dad, Joseph, taught Him to build those mansions we’re supposed to get. I think the rolling greens beyond the golden shore are nurtured by the Gardener and I think Jesus has been aging Wine in preparation for us all celebrating together. I think every chair and table, every house and blanket, is homemade. I don’t think any of heaven will reek of machine or ostentation.

I think the glory of heaven, the weight of it, will be in the majesty of hard, deliberate, intentional work. Cathedrals are like this, full to the brim with homemade masterpieces.

And I think the invitation is for you to spin your own masterpiece, around the breakfast table, with your kids in the car, at your office, and as you do your chores. Heck, even as your weed. Renovate the cosmos, one room at a time, until the whole earth is filled with His Glory.

The Spoils of War

When I got home I barbecued some chicken wings for the family.

Honey garlic, sriracha cesar, and a cajun dry rub.

We had more infused water, and we had carrots and celery, too — just like at the restaurant. We sat on our patio listening to Frank Sinatra and we ate and we talked and the breeze sang through the willow tree.

Life grows sweeter by variations.

A dinner earned does more for the body, and the soul, than indulgence ever could. And I think we need more of that, the beautiful reward of a hard day’s work. It’s easy to see it in the cold beer after a day of cutting grass and raking leaves, but it’s much harder to see in a day pursuing chastity or generosity.

It’s there, though, even if it’s hard to quantify.

Earned beers just taste different, and so does earned rest in the pursuit of the virtues. Maybe we can’t articulate it, but sure as shootin’ we should be able to feel it.

I guess what I am trying to say is :

Do your chores, say your prayers, and clean out your ears.

Do it with a smile and make the world around you more beautiful.

Or else.

Every Day Saints is a torchlight searching for the quiet miracles, the beautifully human stories and ideas that exist all around us. And it is a place to dialogue, not Holy Ground, but still a place of gathering.

I was just thinking about this today while driving my child to art camp. There’s a place along a back road that’s been a hidden green glen for as long as we’ve been living here, and it’s been mysterious. It’s far from any house, has woods on three sides, and it serves no useful purpose. But I’ve loved it because it was beautiful, a little cave of shaded green with thick, shorn grass.

This morning with a dismayed start I noticed that its almost gone- fallen branches half hidden in high grass, all dissolving into general chaos.

Then I remembered the house high on the hill above had sold a little while ago. No one loved that little grove any more. They didn’t know it’s story. The labor required to get down in there and maintain it was not being given, and the beauty was being rapidly lost. It will disappear completely soon and few will even know it was there.

I’m out pulling weeds in my landscape every time I’m outside, but I can’t stay long in any one place yet, because I have to keep an eye on a very mobile two year old. But I will keep on with the labor as long as I can, as well as I can.

God bless you

Today is exactly the day I needed to read this. Your beautiful writing is such an encouragement, particularly when the chores pile up and the work seems interminable. Thank you for sharing.